|

KGGM &

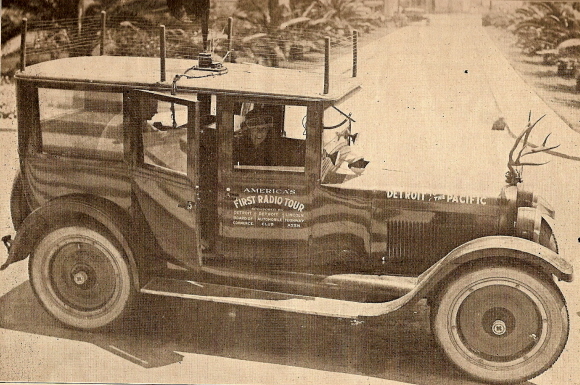

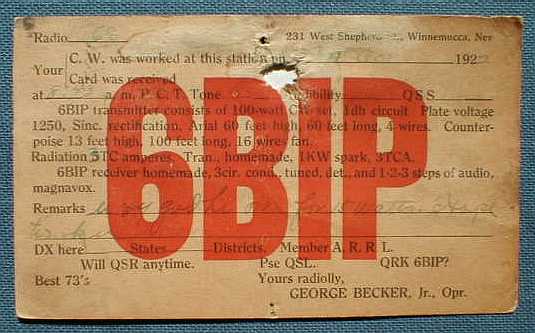

Jay Peters - Jay W. Peters got his start

in radio broadcasting in Inglewood, CA, in 1927, with a portable

broadcasting station licensed as KGGM.

He operated his station, which was described as a "portable set operated from a

truck," on 1470kHz at a power of 100 watts. On April 27, 1928, the Federal

Radio Commission (FRC) announced that all portable stations would be restricted

to operation on 1470kc or 1490kc and eventually they would be eliminated by July

1, 1928. In an Oakland Tribune article from June

20, 1928, it was reported that four California stations, one of which was

KGGM, were to be banned from operating

by the new regulations that would become effective August 1, 1928 (July 1, 1928

according to FRC.) Peters vowed to fight the new

regulations but he would have had to go to Washington DC on July 9, 1928 to "show

cause." With the ban looming ahead, Peters was hired by the

"Bunion Derby - 1928 Footrace Across America", an event put on by promoter,

Charley Pyle. Peters was to provide live coverage of the race as it left Los

Angeles and was to follow along in his portable station as the race progressed

across America. Interviews with the race participants was part of the coverage

along with entertainment from a 12 piece jazz band. When the race reached Albuquerque, New Mexico,

Peters' truck (bus - see paragraph four) broke down. Apparently, the whole event wasn't going very well and

Peters had not been paid, so he decided to leave the portable radio station in

Albuquerque. Peters quickly reached an agreement to sell KGGM to The New Mexico Broadcasting

Company. The call letters, KGGM, were transferred to the New

Mexico Broadcasting Company at that time, August 1928. This was apparently just

about

the time the portable ban went into effect. Peters also sued Charley Pyle for $3183 in

lost wages and other expenses (listed as cost of station in some sources.)

Peters went on to Reno, Nevada to start a new broadcast station. He may have

known that Reno had been without a local broadcast station since the closure of

KFFR in 1924 but this is purely conjecture.

The Myths &

the Facts - A commonly heard version of the story

relates that the call letters KOH were assigned to Jay Peters and his

mobile station in 1922, however there are no Department of Commerce (pre-1927) or Federal

Radio Commission (1927 or later) records showing that the call KOH was

assigned to Peters before September, 1928. The story of an early twenties assignment of

the KOH call to Jay Peters probably originates from a belief that the

Department of Commerce issued all early broadcast stations three-letter calls first,

followed by four-letter calls later, which isn't true. Actually, three-letter calls were

initially issued to ships and commercial shore stations, (an International agreement

dating from 1908.) Due to maritime superstition, ships that met with a disastrous end did

not have their calls re-issued to other ships. Apparently, if the ship was sold to another

country, then the three-letter call was also not re-issued. The first broadcast call

issued was a four-letter call, KDKA, but immediately thereafter, the

Department of Commerce started to issue "retired ship" three-letter calls to

many applicants. Through 1922, while most applicants received four-letter calls, some

stations would be issued the old ship three-letter calls. After 1923, the Department of

Commerce had a change of plan (they had many) and three-letter calls were only issued

randomly, perhaps by special request or perhaps as they became available from recently

retired ships. According to Federal Radio Commission records, the last three-letter call

issued to a "new station" was KOH, issued to Jay Peters on

September 13, 1928. While three-letter calls were sometimes re-issued and changed for

"existing stations" after that, no other three-letter call was issued to a

"new station" after KOH.*

A commonly heard story, (told by Walt Mulcahy), has Peters as a dealer in radio transmitting equipment arriving in Reno to

demonstrate a mobile transmitter/station to investors who wanted to build a new broadcast

station for Reno. Peters found that the investors would not accept an order for equipment

but insisted upon buying the actual demonstration mobile transmitter (which

supposedly was hauled around on a trailer.) The buyers prevailed

and the entire equipment package was purchased and Jay Peters hired to set-up and operate

the new station. Some of the prominent investors were H.E. Saviers and Son, Inc. (Reno's

largest dealer in radios and phonographs), Sierra Pacific Power Company (may have actually

been the Truckee River Power Company at that time) and the Reno Chamber of Commerce. It is

likely that Peters told the story of his KGGM sale in Albuquerque to his

many friends and the location of the sale became confused after the story was retold by

others. The documented evidence has Peter's mobile station, KGGM,

transferred to The New Mexico Broadcasting Company in August 1928.

Another frequently

heard version of KOH's origin supposedly starts in 1927, with Peters building a

mobile broadcast station in an old bus. The antenna was supported by two A-frame masts

mounted on the front and rear bumpers. Though this bus-station was almost

certainly a reality, in this hearsay version, Peters did not have a broadcasting

license and traveled around Nevada broadcasting radio shows using whatever local

talent he could find. When Peters arrived in Reno, he continued to operate his

mobile station around town without a license however he was approached by "radio

officials" who informed him

a license was going to be required and the station had to cease mobile operation

(likely confusion with the KGGM ban of 8/28) The story continues that Peters

applied for a license and was given the call letters KOH.

Except for the bus-station, all of this story is fabrication based on a few

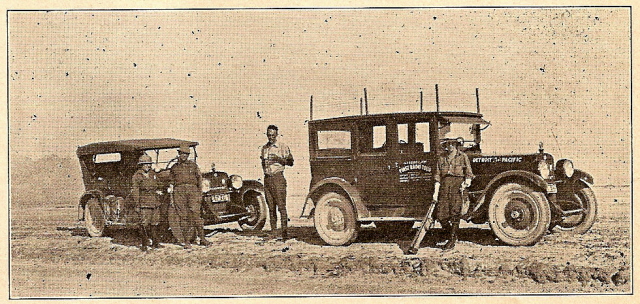

confused facts. The KGGM Bus-Station was likely a reality. The facts are based on a photograph that Peter's had of a

(his) mobile station that was built into a

bus. Robert Brannin had actually seen the photo that Peters had of his

bus-station. An article in

"Popular Communications" magazine mentions that "the bus broke down" when

Peters' KGGM was stranded in Albuquerque (but this is the only reference

to a "bus mobile station" in print.) It is likely that Peters

installed his portable transmitter on a bus specifically for the "Bunion Derby"

trip, after all, he was going to need someplace to stay during the cross-country

trip. As with much of the early history of KOH, Peters' re-telling of his adventures to his friends in Reno (plus the

photograph of the bus) probably became confused in multiple re-tellings by

Peters' friends and consequently we have the Bunion Derby confused with

the August, 1928 Portable Station ban and the ultimate sale of the KGGM

portable (bus) station to The New Mexico Broadcasting Company combined into the

fabricated stories that have become popularly believed myths. The facts are that

all pre-Bunion Derby printed sources say that KGGM was a "portable set operated from a truck"

(Oakland Tribune and the Los Angeles Times) while the only post-Bunion Derby

source (Popular Communications) states that the station was installed in a bus.

These facts along with the Peters' bus-station photo make it likely that the

KGGM bus-station was a reality.

It is most probable that

Jay Peters arrived in Reno in August 1928 (after selling his portable transmitter to the

New Mexico Broadcasting Company) with the intention of building a new radio broadcast

station. The financing probably did come from the larger Reno businesses mentioned by Walt

Mulcahy. The decision was made to set-up the transmitter at Blanch Field Airport. Peters

applied for a broadcast license at that time and was assigned the call letters KOH

on September 13, 1928. The remainder of the KOH story that follows is

from old Nevada State Journal and Reno Evening Gazette articles along with the FRC/FCC

records.

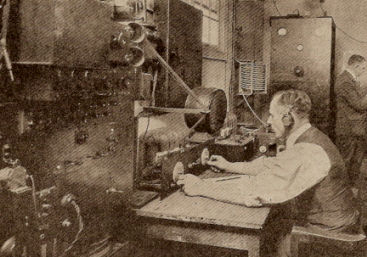

From the

Newspapers - Peters located the

new station's studio in the basement of the Elks' Club on Sierra Street, (he was quite

active in the Elks.) The transmitter was located at Blanch Field Airport. The debut

broadcast was to be on November 11, 1928 (to honor Armistice Day) but on-the-air

testing between 4AM and 8AM the morning of October 27, 1928 proved so successful that KOH

went directly to full-time broadcasting running 100 watts on 1370kHz.** This early

debut also allowed KOH to take advantage of the lucrative political

advertising for the upcoming 1928 Presidential Elections in November. In fact, KOH

even carried the election returns in a joint effort with the Reno Evening Gazette on

November 6, 1928. KOH had a seven man crew, which was the largest for a

radio station in Nevada up to that time. KOH was the first professionally

operated, commercial radio station in Nevada, (the pioneer broadcasters - Broili, Beedle

and Sparks HS/NSJ - were barely more than amateur stations and really didn't net any

income from their stations.)

The Sacramento Bee bought

the KOH operation in early 1931. Apparently, Jay Peters had arranged for

the Sacramento Bee to operate KOH before the actual sale took place. A

REG article of February 18, 1931 states that the sale took place "today." The

actual sale was probably not obvious to listeners since the Bee was already operating the

station anyway. The sale allowed for expansion of the KOH operation and,

by April, new facilities were ready. An advertisment in the REG of April 8, 1931 states

that KOH was now affiliated with CBS and would also run Don Lee programs.

It is still being shown as "operated" by the Bee and owned by Jay Peters, Inc.

Additionally, their new (or rebuilt) 500 Watt transmitter now had "perfect modulation" and

provided static free listening. KOH had moved to the Steinheime Building

near 5th Street and Virginia St. in downtown Reno. With the move came the increase in

power to 500 watts and a frequency change to 1380kHz***, (which gave KOH

a clear channel to the west.) The antenna was located between two, 100 foot tall

wooden poles, one mounted in the sidewalk on Virginia St., the other at the back of the

property. Each pole weighed seven tons! KOH called itself "The

Voice of Nevada."

|

|

In 1939, KOH

applied to the FCC to increase power to 1000 watts and to change operating frequency to

630kHz. Los Angeles radio station KFI (640kHz) filed an opposition but

lost its appeal in December, 1939. KOH had purchased 20 acres in Sparks

for the antenna site and eventually spent $50,000 for two towers, transmitter, station house

(in Sparks) and a new studio at 143 Stevenson St. in Reno. It was August 23, 1940 when the

KOH operation was moved into their new facilities, which featured two

"state of the art" studios at the Stevenson St. location.

The photo to the left shows the

South tower as seen from the North tower. The photo was taken

July 4, 1940 by two men that climbed the North tower. The photo

is looking south from the Sparks location toward what would now

be Hidden Valley to the far left (out of the photo it's so far

left) and Bella Vista Ranch area behind and to the right of the

pond. At this time in 1940, this area was entirely

ranch and agriculture land. The pond probably belonged to the ranch house located off to

the left of the pond (white two-story house) and was probably

fed by Steamboat Creek. This area today is almost entirely

urbanized but the Steamboat Creek water run-off is now directed to the east of Veteran's Parkway and

running down the east side of the valley to the Truckee River.

The photo below right shows

Morgan Morise, one of the two men who climbed the KOH North

tower, on July 4, 1940. Morgan is taking time to wave at the

camera as he is about half way up the tower. Note at the tower

base there are indications of the radial system to the lower

right of the base. Also, note that the rungs that are dominate

in the foreground of the photo are part of the tower-mounted

ladder. Morgan is apparently standing on the tower behind the

ladder and holding on to one of the ladder rungs with his right

hand. |

|

The map below is from a 1943 "Intersection Study"

showing the coverage KOH had running 1000 Watts on 630 KC. The Field

Strength Contours map shows the radiation pattern out to .5mV/M and is similar to the

color coded map on the left. At this time, McClatchy Broadcasting called their line of

stations "THE BEELINE" and it included, KFBK in Sacramento, KWG

in Stockton, KMJ in Fresno, KERN in Bakersfield along

with KOH in Reno. |

|

|

|

|

|

The University of Nevada about 1922

The University of Nevada about 1922