|

Brief History of the Telegraphic

Codes

American Morse was the original telegraphic code developed in the 1840s. Initially,

it is a

code that was to be printed on a Morse Register. Since it was not

aurally received, the code is more difficult than expected and is made up of dots, dashes, longer dashers, even longer

dashers and different length spaces used between some of the dots or

dashes to create certain letters. Once operators learned they were

aurally receiving sent messages in "real time" by listening to the Morse

Register operate, the mechanical printing interface was replaced with a

simple "sounder." However, the Morse code remained the same, since that

was what the operators were "reading." No doubt, the original Morse was

a difficult code to learn and it was difficult to send and receive

without errors.

By the 1850s, sending Morse over

long runs of underwater telegraph cables was proving difficult due to

corruption of the dots due to a factor called dispersion. The distortion

or corruption worsened the faster one attempted to send a message.

Accurate message reception required that the code be sent much slower

than normal, sometimes as slow as only

one word per minute. In order to make the original Morse code better suited to being

sent over long runs of underwater cables required changing many of the

letter and number characters in an effort to

remove all of the variable spacing and different length dashes. This

ultimately "slowed" the code down and allowed more accurate reception. This

revised Morse

code was developed by Ferdinan Gerke and initially it was called

Continental Code. It was adapted by the German telegraphic cable companies in the 1860s.

Continental Code was continually tweaked and improved to allow better

and better sending and

receiving ability. At this time (1870s,) the original Morse code was referred to

as "American Morse" since it was mostly used just in the USA. Continental

Code was used in Europe and the rest of the world. By the 1880s,

Continental was being called International Morse and, by this time, it

was basically the same International Morse we use today.

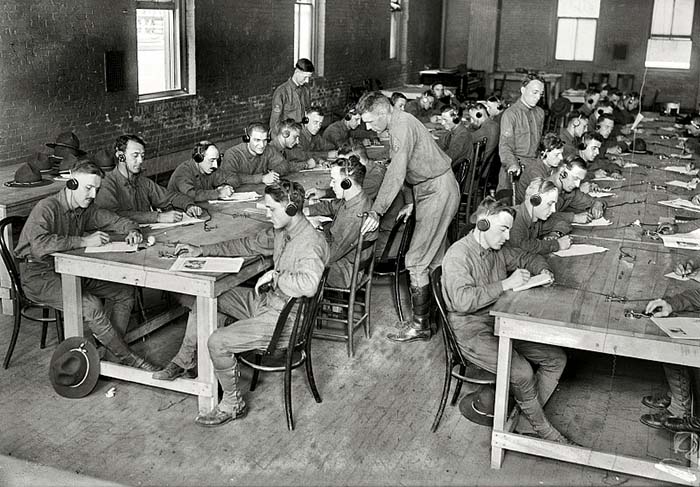

As wireless communications

started, many of the US operators used American Morse. Some types of

wireless detectors only worked relays and sounders, like coherer

detectors. As wireless improved, it was obvious that International Morse

was more suited for damped wave spark transmitters and for reception on mineral

detector receivers. In 1912, the Wireless Conference in

London ruled that all ship wireless messages were to be sent by

International Morse. Most other wireless users also followed this rule.

Hams still tended to use whatever they were accustomed to. Many hams at

that time were also railroad telegraphers and American Morse was

sometimes found on the hams bands.

There was an attempt to make International Morse the standard for

landline users but resistance from companies like Western Union and other wire

companies, who knew that sending messages via American Morse was about

20% faster than International Morse (and also the wire companies didn't

want to have to retrain their operators,) prevented International from

being adapted for USA landlines. Eventually, as communications moved

away from landline wire messages, American Morse wasn't used after the

mid-twentieth century. International Morse has continued on being used in radio

communications both for the military and the amateur.

Here's an example of the difficulty of learning and using American Morse. The

letter T is a dash. The letter L is a long dash. The number 0 is an even

longer dash. The letter P is five dots.

The number 5 is three dashes. The number 6 is six dots. The

letter C is a dot followed by a short space and then two dots. The

letter O is one dot, a long space and one more dot. The spaces can be

three different lengths depending on the character or word or sentence.

To become proficient in American Morse took a lot of time and a lot of

practice. Receiving it is even more difficult. You can send

International Morse and receive it fairly easily on a sounder (as was

done almost everywhere except the USA by the 1880s.) Very late

in the US railroad's use of telegraphic communications, some railroads did

use International Morse but the majority stayed with "railroad code"

until the end. |